Part 3: The General's Network

Gen. William T. Marshall realizes his blindspots

Posted May 6, 2027 - From somewhere in Idaho

My grandad used to sit in this chair and tell us stories of serving under Patton. The wood creaked beneath him as he shifted and gestured and cracked us up. Now I hear it straining and creaking beneath me as I make these notes. No grandkids for me, though. These notes will be what I pass down.

Speaking of granddad, he understood something fundamental about this country: democracy requires maintenance, vigilance, and, occasionally, sacrifice. We’ve forgotten that.

Not me. I won’t forget. This notebook contains names I’ve committed to memory but dare not leave unrecorded. Old habits from my intelligence days—trust memory for the critical, paper for the complex, and digital for nothing truly important.

When I hung up my uniform after 35 years of service—more than a year before the elections—my retirement ceremony had the usual platitudes about duty and honor. What no one talked about was a growing unease about the direction of our institutions—the quiet erosion happening beneath the surface. Not conspiracy, but something more insidious: the gradual redefinition of patriotism as unquestioning loyalty to authority rather than to constitutional principles.

I started making calls a week later. Discreet conversations with trusted colleagues—people whose commitment to their oath I never questioned. Admiral Theresa Reeves was among the first and she was refreshingly blunt after years of Pentagon diplomatic speak.

“About damn time, Bill,” she said when I broached my concerns during a fishing trip in Montana. “I’ve been waiting for someone at your level to say it out loud.”

That fishing cabin later became our first secure meeting location—far from cellular networks, surveillance cameras, and the digital web that increasingly mapped every American interaction. Just two retired flag officers discussing theoretical constitutional crises over bourbon and trout. Nothing suspicious about old warriors rehashing ancient battles.

The network grew organically from there. Adm. Reeves brought in Judge Abernathy, whose judicial philosophy transcended simple right or left politics, but whose reverence for the Constitution was absolute. The judge connected us with civil liberties attorneys who documented increasing executive overreach. Robert Decker from the Agency joined after his resignation, bringing with him analytical methodologies and human intelligence principles that would prove invaluable.

Each new addition followed strict protocols developed during my time overseeing counterintelligence operations—verification through multiple trusted sources, face-to-face introductions whenever possible, and compartmentalized information sharing. Not because we were engaged in anything illegal (we weren’t), but because we recognized how easily legitimate concerns could be reframed as subversion in a shifting political landscape.

The “Lodge” as we called it became our primary meeting ground only after the Emergency Powers Act made our theoretical concerns suddenly, terrifyingly concrete. What had been contingency planning became operational necessity almost overnight.

I remember watching the Supreme Court announcement on a satellite feed in this very room, surrounded by people who understood precisely what it meant. Not just the specific ruling, but the fundamental shift it represented. The Constitution—that remarkable document I swore to defend for almost four decades—reduced to an inconvenient obstacle rather than fundamental law.

“This is what failure looks like,” I said then. “Not invasion. Not revolution. Just institutional surrender via technicalities.”

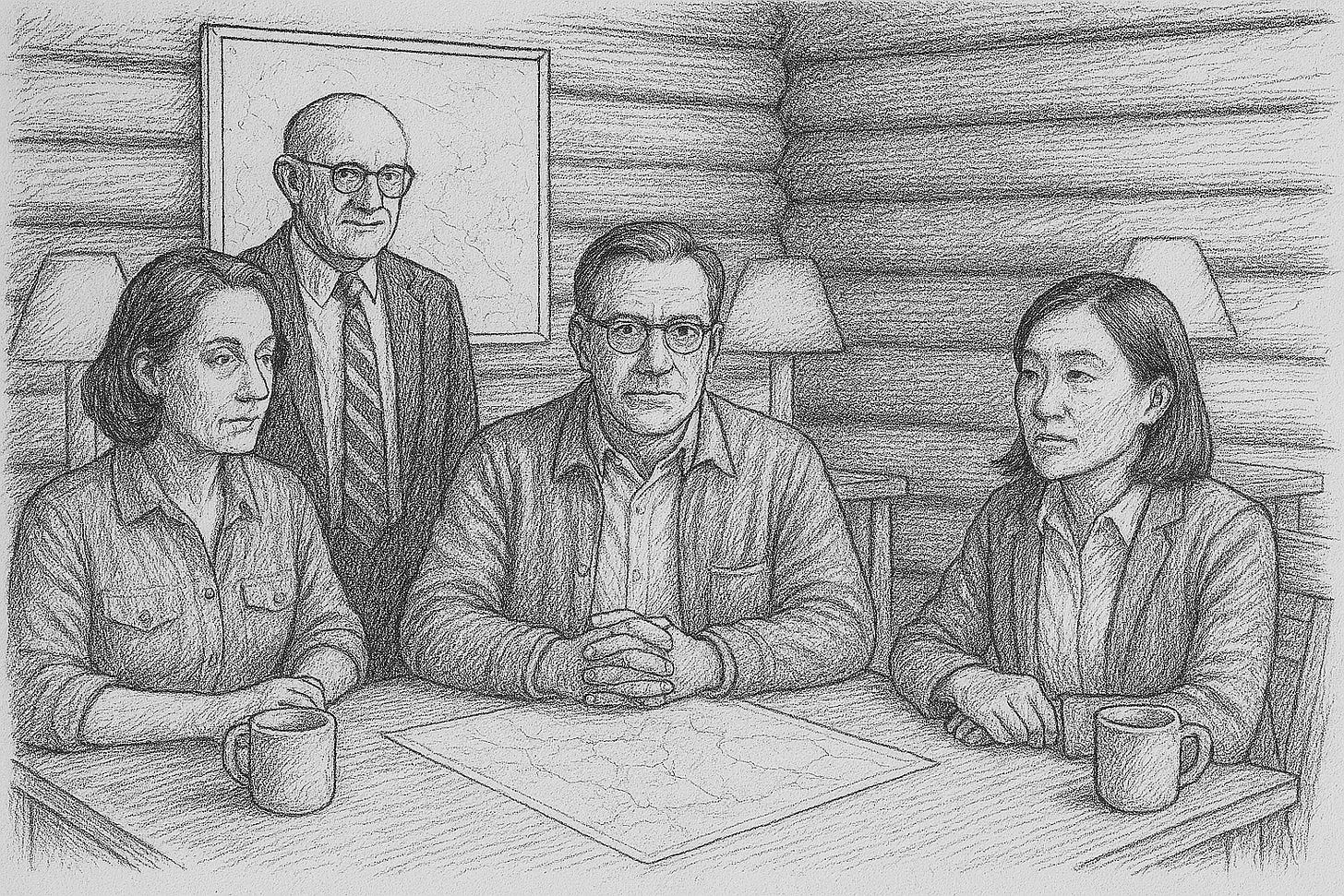

Today, Governor Chen will meet my core team for the first time. I’m struck by how this group defies the caricature that regime propaganda would paint. We’re not angry militia members waiting for the apocalypse. We’re not bitter partisans seeking political revenge. Not foreign-influenced agitators (the regime’s new favorite accusation). We are career professionals with decades of combined experience in governance, intelligence, military operations, and constitutional law. We’re united not by ideology but by recognition of what legitimate authority requires.

Adm. Reeves briefs the group on naval and Coast Guard assets potentially sympathetic to restoration efforts. Her silver hair is pulled back in her trademark severe bun, her bearing still unmistakably military despite civilian clothes.

“We’re not discussing mutiny,” she clarifies for the governor’s benefit. “We’re identifying personnel committed to their constitutional oath regardless of political pressure. There’s a critical distinction.”

Decker follows with intelligence assessment—compiled through what he terms “traditional human methods” rather than technical means. His network of former station chiefs and analysts has been tracking the regime’s increasing reliance on foreign security advisors—particularly those with experience suppressing democratic movements in Eastern Europe and Central Asia.

“They’re importing repression expertise,” he said, pushing wire-rimmed glasses up his nose with an index finger. “Surveillance techniques, psychological operations, crowd control methodologies—tested in Belarus, refined in Russia, now deployed in American cities.”

Judge Abernathy offers the constitutional justification for our efforts. At 72, his voice still commands courtroom attention, his legal mind undiminished by age.

“We are not revolutionaries,” he emphasizes, echoing my earlier words to Chen. “The legitimate constitutional authority resides with elected officials who have been unlawfully removed.” He gave Chen a pointed look. “Our effort is fundamentally conservative—preserving constitutional continuity against illegitimate disruption.”

The discussion turns to strategy, revealing the fundamental tension within our network. Col. Diana Winters, my former counterinsurgency specialist, advocates direct action against regime infrastructure. Her experience in Afghanistan and Iraq shapes her perspective—asymmetric operations targeting communications systems and supply chains.

“You can’t negotiate with authoritarians,” she argues, pacing near the stone fireplace. “They understand force and disruption. Nothing else.”

Pastor Michael Thompkins—whose rural church network has become an underground transportation system for dissidents facing arrest—presents the moral counterargument.

“The minute we use their methods, we concede the moral high ground,” he says, Mississippi accent still strong despite decades in the Northwest. “Violence, even against infrastructure, validates their narrative about us.”

I watch Chen during this exchange, measuring her response. Governors, successful ones anyway, develop can balance competing interests while moving objectives forward. Her political instincts don’t disappoint.

“You’ve both got a point,” she said after some thought. “But neither is sufficient. Colonel Winters is right that regimes understand force—but Pastor Thompkins is right that our legitimacy depends on moral distinction.”

She stands, moving to the large map covering one wall—a topographic representation of the western United States marked with colored pins indicating various network assets.

“What if we combine both elements in our strategy? No violent insurgency, but no passive resistance either. We need a coordinated campaign to disrupt systems, provide services and build legitimacy.”

We watch as she seems to pull together the idea in real time. She outlines a three-phase strategy drawing on historical resistance models. I recognize elements from successful campaigns in Eastern Europe, South Africa, and Southeast Asia—adapted to American geography and political culture. She manages to bridge military strategic thinking with political reality and I found myself reevaluating my initial assessment of her.

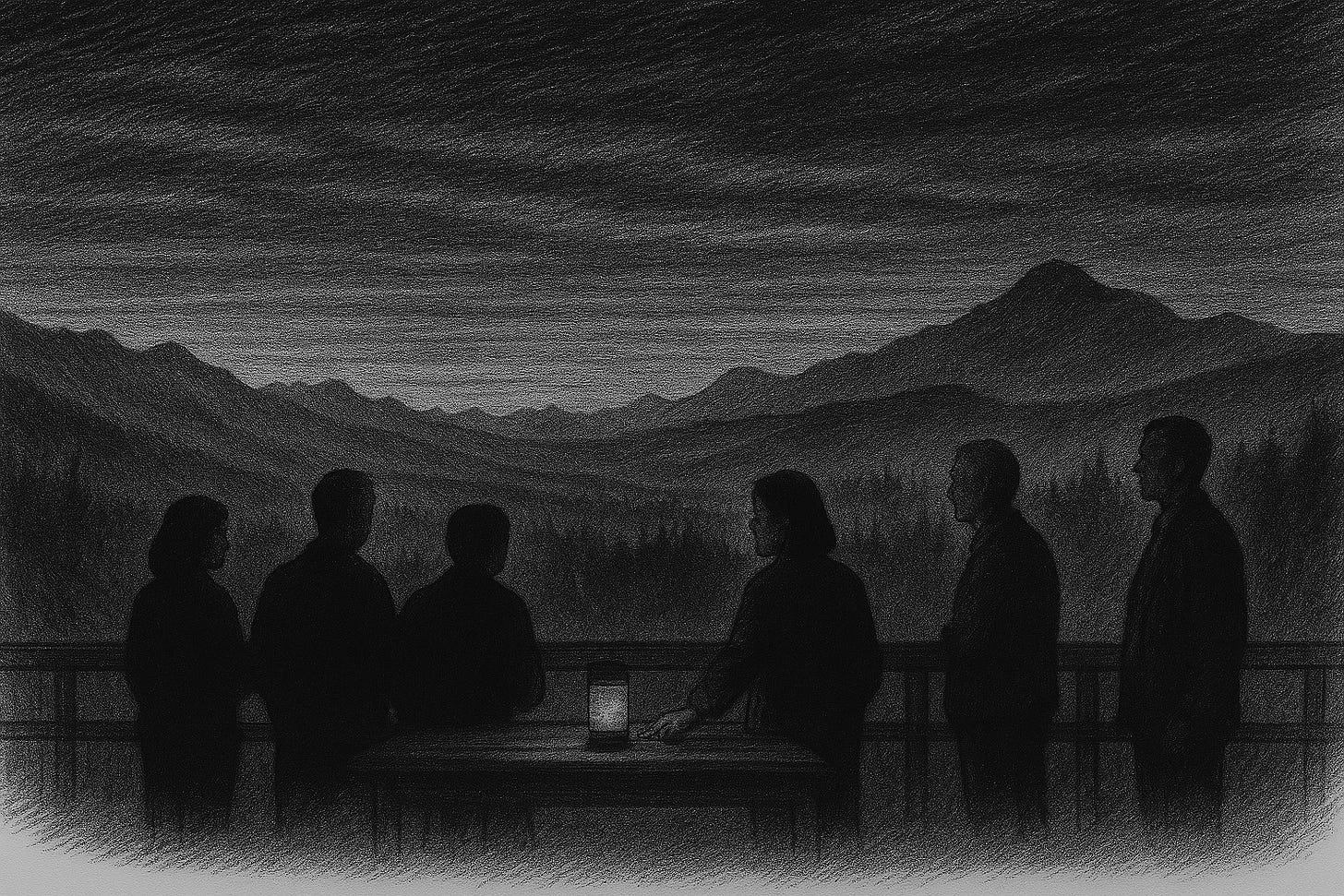

Later, after dinner, I find Chen on the upstairs deck, looking toward distant mountains now vanished in darkness.

“You’ve done good work setting up your network, Bill,” she says without turning. “But there are fundamental flaws.”

“I’m aware,” I respond, joining her at the railing. “Which one concerns you most?”

“Too elite,” she says simply. “Too many generals, judges, and politicians.” She chuckles wryly. “We need ordinary citizens. These kinds of resistance movements only work when coalitions bridge class and cultural lines.”

The assessment stings because it’s accurate. Our network has prioritized security and expertise. We’ve built a shadow national security apparatus, not a people’s movement.

“That’s why we need you,” I finally say. “You can reach people we can’t. We need your political instincts to complement our operational capabilities.”

She nods slowly, still looking into the darkness. “I saw a teacher in Oregon not long ago—Susan Keller. Arrested for using unauthorized history materials. The townspeople stood witness to her detention. No protest, no violence—just … watching. Silently. Like, ‘We see what you’re doing, and we’ll remember.’ It was powerful. Even the agents felt it, I’m sure. We need to harness that power.”

Chen’s insight resonates with something I’ve known but failed to fully integrate into our planning. Successful resistance isn’t just about operational security and strategic objectives—it’s about people’s psychological transformation. The moment when collective determination overcomes individual fear.

Tomorrow, we’ll continue strategy sessions with this new perspective. Chen will meet with our communications team—former public affairs officers now developing secure information channels. Colonel Winters will present regional vulnerability assessments. Judge Abernathy’s legal team will continue drafting restoration frameworks for when constitutional governance returns.

But tonight’s conversation has shifted something fundamental. We haven’t been thinking broadly enough. A successful restoration won’t come through the plans of retired generals and judges alone but through thousands of Susan Kellers and the communities willing to stand witness with them.

During my military career, I learned that the most important strategic adjustments come from recognizing your blind spots. Perhaps that’s why, despite all the uncertainty, I feel more hopeful tonight than I have in months. We’re building something that might actually work—not because it’s tactically brilliant, but because it connects to something deeper in the American spirit that no emergency decree can extinguish.

The night watch is changing shifts outside. Time to secure these notes and get some rest. Tomorrow brings new challenges, new adjustments. The road to restoration is long and uncertain, but for the first time, I can see a path forward that doesn’t rely solely on the expertise of old warriors, but on the courage of ordinary citizens.

Comments disabled for security reasons. If you're reading this, share only through secure channels.

Full disclosure and very important

I used AI (Claude, ChatGPT, Gemini) extensively in developing this series. I used it as a research assistant in pulling together the various histories of dissident movements and developing an action plan for the current context. I used it to brainstorm the story arc and plot outline. I even used it as a writing assistant. I didn’t write every word, but I did write a lot of it. As a writer, I have very mixed feelings about this new mode of working, but I think it is the future of AI-assisted writing and research, and the sooner we figure out a way to use it ethically and productively, the better.